Transformasi Indonesia: See, and believe

Photo by Robin Noguier on Unsplash

As a team, we’ve always viewed Indonesia as a great opportunity, both in terms of investments and the potential to grow our business. That was evident enough from our introductory note on Indonesia last week. We thought we’d known everything that needed to be known about the country, with no room for surprise.

We were wrong.

Four days of back to back meetings later, we are convinced that Indonesia is the poster child for what the full potential of every other emerging market ex-China can be. They say it’s all about perspective - and perspective was what we got as the week progressed.

For one, Indonesia could very much be the poster child of the potential that Emerging Market economies offer: a stable and functioning democracy (it’s been 21 years since Soeharto’s resignation marked the end of a 31 year dictatorship in 1998), inflation and rates broadly under control, stable FX for the past 5-6 years and GDP growth at a healthy 5-6% per year, attractive given the size of the market c. 260m people.

The western-centric consensus around Indonesia is misleading (or misled), with the conventional mantra repeating a litany of misgivings with the country: lack of market depth, excessive state intervention, populism in reforms, dominance of state-owned and dynastic family enterprises in capital markets. The list goes on. If the consensus is to be believed, one would be forgiven for concluding that Indonesia was a kleptocracy whose only redeeming feature was an attractive headline growth number, deserving of the occasional spurt of “investment tourism” when the index rises, but not of a long-term capital allocation.

These narratives are self-fulfilling, as Indonesia’s weighting as a country was unfortunately reduced again by MSCI on the Emerging Market index, to make way for A-shares.

The only ones losing out here are investors.

The benchmark index is wrong, guilty of misrepresenting the (lack of) opportunity, and equally guilty of distorting the healthy functioning of the market.

The energy and light of Jakarta by night (Photo by Gede Suhendra on Unsplash)

Let’s set the record straight, starting with politics.

The overarching worry for the investment establishment is a fear of a return to conservative nationalism, in the same vein as President Duterte calling for a renaming of the Philippines to “Maharlika”, ostensibly in an attempt to wipe away its colonial past, but also an echo to former dictator Ferdinand Marcos who proposed the same name, underscored by Duterte’s choice of Marcos Jr. as his vice presidential running mate for the upcoming election. Given the developments in the rest of the world, the UK included, this is understandable especially for managers far removed from the ground.

We aren’t election pundits - we wouldn’t want to even try. But the mood on the ground certainly didn’t give us any reason to believe there was significant discontent. Compared to the mood after the Jakarta governor’s election in 2017 - when there was a palpable sense of discontent especially among the conservative business groups - the atmosphere on the ground this time was one of contentment. Camp Jokowi is strongly in the lead, with election day less than 2 months away (17 April), and the business lobby which traditionally backed the conservative (Prabowo) over the liberal (Jokowi) has flipped sides.

Hot off the press just this week was a snippet from a presidential debate (link to the video in Bahasa on CNN here) during which Jokowi asks Prabowo about his thoughts on Unicorns. The stumbling response, eventually asking to clarify if it was a reference to the “online-online” ones (rather than offline, physical unicorns) made the rounds on Indonesian social media, underscoring what many see as a disorganised opposition. Fingers crossed.

Go-Jek workers riding their unicorns through the streets of Jakarta.

Unicorns make a good segue into our second observation: that Indonesia is not a follower, but rather a leader in the region when it comes to fintech.

Indonesia is already home to prominent headline unicorns like e-commerce giant Tokopedia (US$5.9bn valuation Series G), Ride hailing and payments provider Go-Jek (US$8.6bn at Series F) and Expedia-backed online travel gateway Traveloka (US$4.1bn most recent valuation), to name a few. Additionally, it is the largest market for regional heavyweights like Shopee (part of US-listed, Tencent-backed SEA Limited) and Singapore-based Grab, itself worth north of US$10bn following its most recent round.

The joy of a unicorn-filled Jakartan traffic jam explained by Three Body Capital CEO, David Cunio.

These companies attain their scale and valuations not by coincidence. Indonesia’s market size matters, with 141m out of 264m of the country’s population living on the main island of Java itself, giving these service companies a critical mass of demand to cater to. But size isn’t everything. Indonesian startups have shown an amazing ability to innovate and adapt to local conditions, rather than simply copy-pasting business models out of the playbooks of Silicon Valley or the Chinese internet giants.

For example, Go-Jek built its business out of something that was uniquely southeast asian: motorbike taxis. On that base they built payments and services offerings that catered to Indonesia-specific practices (e.g. dealing on whatsapp, paying by bank transfer and getting a Go-Jek rider to deliver the purchased goods), supplying the infrastructure for the unbanked to access payment and transactionary facilities in the process, including allowing Go-Jek riders to act as deposit takers (cash for Go-Jek credit), circumventing the lack of banking infrastructure and bank account penetration outside urban areas in their very own way.

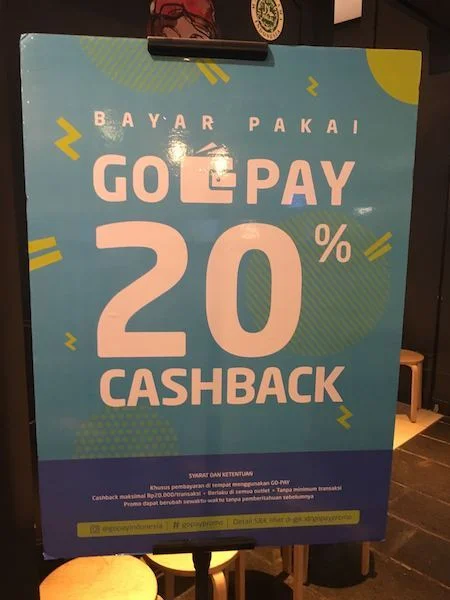

At the same time, they know when to take a leaf out of the China playbook when they need to: take a stroll through any of Jakarta’s mega malls and you’ll see banners and posters advertising cashback and rebates for spending at restaurants. Traditionally, these posters were put up by the likes of CIMB, Mandiri, Citibank, BNI or BRI, competing with credit card offers of up to 20% off for cardholders. Recently, their banners have found new neighbours: Grab’s Grab Pay, Go-Jek’s Go-Pay, Lippo’s OVO and Alibaba’s Dana are the most prominent of the new e-wallet offerings in town. Their value proposition: anything from 10% to 50% instant cashback when paying with their system.

We’d be disingenuous if we claimed to be able to tell which one of them will win the fight for user acquisition. The winner is uncertain, but the losers are crystal clear: the traditional banks and their credit card businesses. With the lucrative fee income from credit cards under threat (it’s not just unbanked/low credit score customers using these e-wallets: EVERYONE is using them), banks can start preparing their farewells to these high ROE and high growth contributors.

For those who look at China and say their transition to cashless was sudden and happened at a blink of an eye, wishing that they had seen the early signs, rejoice: these are the early signs, right here on the mall pavilions of Jakarta.

The queue for Häagen-Dazs, Jakarta.. 62% cashback from BCA is quite a draw!

This takes us to observation #3: that the public markets in Indonesia are failing investors.

Nowhere is it more obvious than in the fintech space: none of the winners are available for any domestic investors to buy. In fact, they’re not available for foreign investors either, unless your company’s called Sequoia, Softbank or GIC. The Indonesian stock market is an ossified monolith to the old economy. At least the banks are still available for hedge funds as shorts.

But the market failure extends way beyond lack of investment opportunities. It is also failing to serve as a price discovery mechanism for smaller companies to raise capital.

What was previously the de-facto channel for small private companies to raise equity funding by going public has become at best a casino (where pump and dump/pump and place schemes fuel midcap bubbles), if not a bottomless pit of equity dilution. Nowhere is mispricing more pronounced than real estate assets owned by developers and conglomerates, which have a market value of anything from 30-70% discounts to NAV. Discounts aren’t problems if they are temporary - they are huge problems when they are permanent.

Where abundant buyers and sellers would historically come together and try to “discover” the “right price” of these assets, all these assets attract these days are punters looking for a pump and dump opportunity.

Everyone else has become an index hugger, hugging the liquidity index LQ45 tightly, scrounging for performance against a market that is increasingly driven by ETF flows which funnel liquidity (not surprisingly) only to the largest companies on the JCI, reflecting the undifferentiating whim of the unknowledgeable, one size fits all ETF buying tourist investor, popping in for a couple of weeks in a bout of fomo, and selling out once valuations mean revert.

The frustration that smaller companies face as a result of this market failure is understandable: with no channel for price discovery, they are forced to finance and sell off assets at large discounts to intrinsic value, with little chance for ever realising the true value of their assets.

The knock-on effect of this is that the investment product offering to domestic investors is one dimensional and largely index-hugging. In a crisis of un-differentiation, investors understandably see no value in stock-picking, and move towards more un-differentiation, trapping themselves in a permanent spiral of ETF-fuelled correlation to the most aberrant of price drivers: global macro flows.

And in their search for improved returns, domestic investors, including HNW individuals and their family offices, are turning to ever-higher risk profile products, including PIK bonds and equity-backed financing schemes that promise USD returns in the mid-teens or higher.

Warhol's, The New Spirit, on display at Jakarta’s, Museum MACAN. New spirit indeed…

What now?

Thanks to our friends and networks in Indonesia, we have had the opportunity this week to meet with some of the most prominent business people and investors in the country. These conversations, and the time spent exploring the city from our humble base at the Artotel Thamrin (highly recommended at only £35/night, in a great location no less!), inform our perspectives and our investment views.

The insights are multiple fold, but if there’s one thing we need to take away from this trip it’s the fact that Indonesia is simultaneously offering AND seeking immense opportunities for capital to seek superior returns. From regional heavyweight unicorns to island resorts off Bali on offer on one hand, to European properties and the best of Silicon Valley in demand on the other.

And last but not least, huge thanks go to our friends in Indonesia, some of whom we’ve known over almost a decade of doing business together, for the opportunities that we’ve had to meet some of the most brilliant minds in the country this week.

A finally huge thank you to everyone who’s made time to meet us this week - your time, advice and feedback is much appreciated and we look forward to doing business with you in the months and years to come.

Bhinneka Tunggal Ika.