They came from behind

Photo by CloudyPixel on Unsplash

Such were the famous last words of Gold Squadron Leader Jon “Dutch” Vander before his Y-Wing bomber got taken out in the Battle of Yavin.

Thankfully, as scripts often go, Luke Skywalker at the last minute successfully launches two proton torpedoes into the exhaust port of the Death Star, destroys the planet-obliterating space station and saves the Rebel Alliance base on Yavin.

Star Wars Episode IV was (and is) one of the classics in the entire Star Wars saga, which recently concluded its official canon with Episode IX: The Rise of Skywalker. Mixed reviews depending on who you ask, but certainly not a shabby effort.

As far as we’re concerned, there’s a risk that something else “comes from behind”. We mentioned it when we discussed gold, former Fed chairman Ben Bernanke mentioned it in 2010, and it’s starting to show signs of emergence.

That thing is inflation.

But everything is now more affordable than ever before, what with Amazon, online shopping in everything from fresh groceries to detergent, budget airlines, cheap taxis and even music – we must be mad to be going on about inflation.

In that context, it’s true: technological improvement in large swathes of the economy, in particular logistics, production and data management/tracking, have led to efficiencies that facilitate the continued decline in costs of just about everything. From the weekly grocery shop to booking flights directly with airlines, from streaming on-demand music and films to grabbing an on-demand car for a couple of hours – life has in many respects indeed got cheaper and better.

And we have become quite used to it. Unfortunately, there’s nothing in the rulebook that says this can (or should) be a permanent state of affairs.

Putting inflation in context.

Regardless of how much one reveres or detests the idea of a central banker, there are some things we can always agree on. That they’re very much human, like the rest of us, and that they’re usually in their 50s or beyond. Mark Carney, the former governor of the Bank of England, has the honour of being the Youngest Central Bank Governor to be appointed (at the time), when he was 48 years old.

And being human leaves them with the memories and biases that come as part of the package, in particular the notion that while inflation is bad, deflation (look at Japan and its lost decades!) is even worse, and that the magic formula for economic stability, spawned from the consensus of the 1980s and 1990s, was “low and stable” inflation, which – in recent years – has come to settle at the largely arbitrary number of 2%. Why 2% as an inflation target? The more important question is: why target inflation rates in the first place?

After the end of the Gold Standard, New Zealand was the first country to adopt an inflation targeting mechanism in 1990, followed by Canada in 1991 and the UK in 1992, after exiting the European Exchange Rate Mechanism on Black Wednesday. With some reflection on the accepted orthodoxy of economic policy, the reasons become quite clear: in a post-gold standard global economy fully based on fiat currencies, anchored largely around the US dollar (which itself is fiat), the easiest way to promote exchange rate stability is to maintain a stable inflation rate, removing the purchasing power arbitrage that causes exchange rate volatility.

Once the bulk of central banks have it in their heads that 2% is the inflation target they wanted, then any economy with inflation above 2% would see consistently depreciating foreign exchange (think Zimbabwean hyperinflation and the corresponding depreciation) and any economy with inflation below 2% would see consistent appreciation, everything else equal. 2% was an arbitrary number – but it has also become the arbitrary equilibrium.

Conspicuous by its absence is a list of countries that have had sub 2% inflation over a sustained period of time, or a list of currencies that have been constantly appreciating over the years. It seems they don’t exist, but we can take a guess at possible candidates. There is one easy way to mask an appreciating currency: sell more of it in exchange for another currency, build up reserves of foreign currency and keep the face value of the domestic currency intentionally low. A little like this:

Source: People’s Bank of China Data

Given the current political landscape, it’s easy to get into the discourse of currency manipulation etc. That’s not the point we want to drive here.

The point is this.

Over the past 30 years, the world has moved into an inflation targeting regime, explicit or otherwise, that says to central bankers “keep inflation at 2% and you’re doing your job well”. Such a mandate, well-meaning as it is, ignores and masks the fact that the past 30 years have been singular in terms of the entry of large swathes of low-cost-of-production economies entering the global economy. Nothing like the industrial revolution, but good enough for modern memory. Add to that developments like semiconductors and the internet and we have a cocktail of rising productivity, accelerating growth AND falling prices.

China is the key example, but take everything from the former Soviet Union to Southeast Asia to India to Africa, and it becomes clear that what was branded the “growth” story in emerging markets was really the story of these economies entering – sometimes shakily – into the club of globalised economies, exporting their low costs of production as disinflation, and allowing global inflation to enjoy a profile such as this:

Source: World Bank

So far, so good, at least on the aggregate level. Beyond doubt, most people around the world have seen their quality of life improve significantly over the past 3 decades. Falling inflation is a good thing, especially if it’s driven by a huge supply-side improvement, leading to job creation and technological advancement for everyone.

But the rules, we must follow them.

Remember the 2% inflation target? That’s great, but inflation has been below 2%. And it needs to go up, so easy monetary policy must continue.

From the minutes of the Fed meeting in December, released early January, we read:

“Total consumer prices, as measured by the PCE price index, increased 1.3 percent over the 12 months ending in October. Core PCE price inflation (which excludes changes in consumer food and energy prices) was 1.6 percent over that same 12-month period, while consumer food price inflation was lower than core inflation and consumer energy prices declined. The trimmed mean measure of 12-month PCE price inflation constructed by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas remained at 2 percent in October. The consumer price index (CPI) rose 2.1 percent over the 12 months ending in November, while core CPI inflation was 2.3 percent.”

And that despite multiple measures of inflation already starting to push above their 2% target, because their chosen measure of PCE remains below the 2% level:

“Participants also discussed how maintaining the current stance of policy for a time could be helpful for cushioning the economy from the global developments that have been weighing on economic activity and for returning inflation to the Committee's symmetric objective of 2 percent. Participants generally expressed concerns regarding inflation continuing to fall short of 2 percent. Although a number of participants noted that some of the factors currently holding down inflation were likely to prove transitory, various participants were concerned that indicators were suggesting that the level of longer-term inflation expectations was too low.”

With the conclusion being that:

“The Committee judges that the current stance of monetary policy is appropriate to support sustained expansion of economic activity, strong labor market conditions, and inflation near the Committee's symmetric 2 percent objective. The Committee will continue to monitor the implications of incoming information for the economic outlook, including global developments and muted inflation pressures, as it assesses the appropriate path of the target range for the federal funds rate.”

It turns out that setting numerical targets for something as nebulous as inflation isn’t really a good idea, especially when that target is adhered to, correct to two decimal places.

Pick and choose.

Ask any economist and they’ll be pretty quick to agree that the conventional measures of inflation are just convention: some countries use the consumer prices (CPI), others decide to use retail prices (RPI), while others use wholesale prices (WPI). In total there are at least 10 different measures of inflation that one can look to so while we decide by convention to use CPI above, these numbers are far from realistic.

One of the most interesting gauges of price levels in India is perhaps the Onion price – don’t believe how important it is? It’s important enough to start Onion wars. Courtesy of our friends at Edelweiss, we have an Onion price tracker for India:

Source: Edelweiss, Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE)

Even disregarding that spike at the end (which recently coincided with an official inflation print north of 7% in India), contrast India's Inflation profile to these ones:

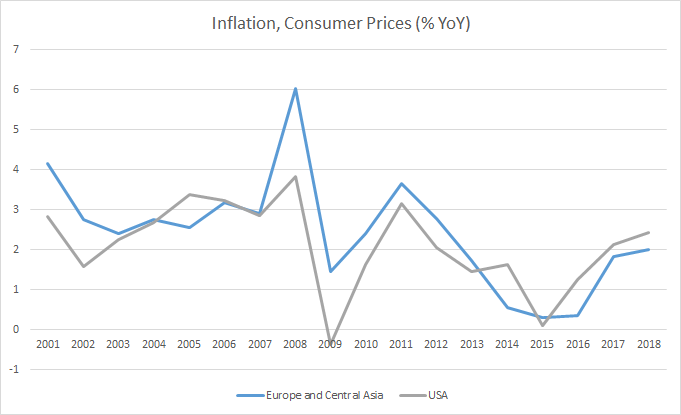

Source: World Bank

Volatility aside (the India data is monthly vs annually here), a clear trend is showing:

The 2% inflation target seems to be working, with Europe and the US converging towards the 2% level.

There are massive economies around the world, like India, who have not had a shortage of inflation and who are bearing the impact of loose Fed and ECB liquidity in their numbers.

On average, across the US and Europe, two of the largest economic blocs in the world, inflation has already picked up from its lows in 2015 and is actually rising.

Just like in India. Just like in China.

If we still think they were still exporting deflation to the rest of the world, that’s a view that’s about 5 years out of date. Inflation is low compared to history, but at the same time, Chinese inflation looks like it found its bottom a couple of years ago:

Source: World Bank

Cheap labour? Think again. Labour costs in China have been rising too. Average annual wages across the country (urban sectors only) have risen from Rmb 5,348 in 1995 to Rmb 74,318 in 2017. In Beijing, the number is Rmb 131,700, which is by no means a shabby number. Looking at the figures over time:

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

We’ve enjoyed 3 decades of structural disinflation, thanks to the “emerging market” bloc of economics being globalised, as well as technological innovation of the highest order. At the same time, our central bankers’ dogged focus on that 2% inflation target, particularly in the monetary abundance of the past decade, has allowed monetary conditions to be extremely loose, perhaps excessively so, without taking into consideration the fact that this re-integration of “emerging markets” and the “internet revolution” are a one-off events, the exception rather than the norm.

The world changed, if only for a decade, but the rules didn’t. And now we might need to clean up the excesses.

The spirit of rules.

There is no shortage of market commentators, pundits and opinions who proclaim the gospel of change, or the prophecies of impending doom. And central bankers, above all, need to distance themselves from the noise in order to fulfil their job of keeping prices and the broader economy stable.

The keywords here are “prices” and “the broader economy”. Central banks manage liquidity and the availability of credit. Not “the stock market”. Not “the business cycle”. Not the fates of any business, big or small.

The risk that we all face is that “the economy” and “the stock market” have become conflated to mean the same thing in everyone’s heads, not unlike what we described when we looked at risk drift – including those of the central bankers. We aren’t experienced in the field of monetary policy management, so we’d be the last to claim that we can do a better job, but the question needs to be asked: at 1.6% inflation on a single inflation measure, with every other inflation measure ticking above the (albeit arbitrary) 2% target, is an accommodative monetary policy stance from the Fed and the ECB, among others, given where their inflation gauges sit, accommodative to the real economy or to the stock market?

Has the spirit of the rule, to aim for 2% inflation as the proxy for “low and stable”, become a convenient excuse to keep the business cycle going for as long as possible, while maintaining the narrative that “inflation remains low”?

What happens when the business cycle inevitably turns and there is insufficient dry powder (room to cut rates, or expand the central bank’s balance sheet) available to stabilise the actual real economy?

What if long-awaited inflation comes, but growth doesn’t?

Earlier we wrote about good and bad inflation and deflation:

Good inflation is what central bankers seek, the coveted “low and stable” 2%.

We’ve had decades of good deflation, even though we probably didn’t notice it.

Bad deflation is well-covered in economics textbooks, and is rightly feared. It looks like what happened in Japan, where a lack of economic activity and shrinking GDP simply tipped the country into a falling price spiral.

That leaves us with “Bad Inflation”, which comes in two forms. One form is hyperinflation, runaway inflation like what we know of in Zimbabwe and post-reunification Germany.

Bad inflation has a second form: Stagflation.

Stagflation = Stagnant Growth + Inflation.

That’s the kind of inflation that drives prices up, while unemployment also rises, such that when it comes to real growth, has near zero net effect. The kind of inflation that is debilitating to an economy, because costs are rising with very little/no incremental growth in productivity and employment.

Ultimately, if we do get into a stagflationary environment, what will the rules that govern the central banks tell them to do? At 4% inflation, do we take rates up and crush credit availability and growth? After all, the rules say they need to bring inflation to 2% – do they remain obedient to their rules, as they do now?

Governments could come in and help to give things a push – build some highways, infrastructure, maybe some handouts? And if they’re broke? Let’s just borrow. No matter that the global debt load is already 322% of global GDP, public debt is rising all across the world or that the US public debt balance sits at an eye-watering (try saying the number, here’s a tip) $23,205,946,266,407 and counting (even 2% interest on that much debt matters) or $70,253 per capita. After all, with interest rates at all-time lows, and everyone happy to lend to everyone else to keep the music playing, kicking the can down the road seems like a good idea. A 100-year bond perhaps?

No, it’s not a joke. In case you missed it, the US Treasury Secretary did float the idea of a 100-year US Treasury Bond. At the very worst, there’s the option of using inflation to deflate the real value of the debt.

To be honest, we don’t know what the right policy moves should (or could) be. All we know is that the signs of inflation, absent for the most part of 10 years, are starting to show – starting in the commodity space with the likes of sugar, copper and gold. Working out whether this is good or bad inflation is important – but even more so is being prepared for inflation in the first place.

As far as we can see, everyone is starting to get very used to the benign environment of the past decade. If inflation does sneak up on us from behind, we should at least have a plan to deal with it.