It ain’t crazy, it’s just not human

Photo by Phillip Glickman on Unsplash

Take a tour of the financial Twittersphere and you will find no shortage of litanies about how the market is broken, and how this current market is ridiculous, untenable and doomed to collapse.

The disconnect between the market and the economic realities has left the large majority of professional investors completely bewildered; what happened to “fair value”? In fact, what happened to “value”? More importantly, is there no more common sense left in this liquidity fuelled market?

We’ve had prior discussions on how to value value. Those observations continue to become more and more pertinent in this market. But the question this time is a slightly different one: not how, but who? As the dichotomy between the economic reality of our COVID-19-ravaged world and that of the financial markets continues to grow, the question that is on everyone’s mind is, with everything that is happening and that could potentially go wrong even from here, who on earth is doing the buying, driving stock markets to all-time highs?

We need to qualify our question again. It’s not a question of who is behind the buying, but rather, what? Because in all likelihood, what’s behind the buying isn’t human.

A brief history of stock picking.

Speculation and stock picking has captured the imagination of the general public for many decades now. The underlying principle is quite simple: discover something that no one else knows is valuable (e.g. earnings potential, new technology, a potential takeout) and put on a position ahead of everyone else discovering that same fact. If you’re right (and did it without violating any rules around insider information), you make a lot of money as price converges to value.

Going about this process can take many forms, the most well-known of which is that espoused in the Benjamin Graham school of value investing, made famous by his greatest disciple, Warren Buffett. Other approaches exist as well, from the factor models of Fama and French to the slightly more esoteric annals of Black and Scholes, which don’t always end that happily. Regardless of how one goes about discovering value, the fundamental assumption is that value matters, and that value ultimately determines the outcome of prices in the marketplace.

All this sounds pretty reasonable. After all, if you could buy a $100 note for $50, and then use it to buy $100 of groceries, that’s an absolute steal, and the seller of the $100 note must be crazy, or stupid. Conversely, if you could sell a $50 note for $100, and take that money to buy two $50 notes, you’d be twice as well off as before the transaction, and the buyer of that $50 note must also be crazy or stupid.

Either way, whether you’re pricing real assets, stocks or even complex derivatives, the underlying principle is the same: the no-arbitrage condition has to hold, stipulating that if prices were to allow an arbitrage trade to happen, gaining the trader a riskless profit, then surely those prices cannot hold as more and more traders come into the market, repeating the trade until the pricing error disappears, resulting in fair value being reflected in the price. This is the role of market makers – the arbitrageurs who scrape the financial markets for great deals from poorly set prices for consistent, small but ultimately riskless rewards.

The unspoken assumption in all of that above is that the entire market is largely human. Yes, there have been algorithms and quantitative programmes that run in the market for years with great success, most notably Jim Simons and Renaissance Technologies (the key word being “technologies”), but until recently their tendencies have also been human: find the right price for the asset in question, buy if it’s too low, sell if it’s too high.

Wall Street (and every other financial district in the world) used to be crawling with analysts and brokers who would profess to have some interesting insight on a certain company: a potential earnings beat, the chance of a special dividend or the probability of a generous payout from an acquirer. They had a job only because people cared: the “buy-side”, armed with billions of dollars of assets entrusted to them on a mandate to find the best companies and the best ideas, wanted to know these things, because whoever got to that information first could get a position in place, and benefit from the buying of whomever got there afterwards and sell out at a higher price.

Enter the passive brigade.

The financial crisis of 2008-09 did no favours to this illustrious community of pundits. Investment bankers and stockbrokers were vilified as greedy vulture capitalists who ripped their clients off, but so were their clients. The buy-side wasn’t spared either. The overarching narrative grew into the one that continues to dominate today: democratise investing, scrap complexity, put a simple market tracker into the hands of everyday investors because stock picking is dangerous and they’re better off buying a broad, diversified basket of instruments.

Such a narrative has its roots in many of the traditional tenets of active management: indexation (and fundamentally, diversification) comes from the work of Harry Markowitz, which underpins the asset allocation decisions described in the Capital Asset Pricing Model. “Buying the market” is furthermore a Warren Buffett preaching, what he calls “a cross-section of the American economy”, somewhat ironic given the Berkshire Hathaway portfolio of assets bears no resemblance at all to the S&P 500, of which the Oracle of Omaha never fails to extol the benefits of owning.

If while reading this you’re starting to detect a gradual creep and a slightly uncomfortable sense of inconsistency, you’re not wrong. Bring in the oft-quoted father of ETF investing, Jack Bogle, the founder of ETF provider Vanguard, and we start seeing how different the entire notion of passive investing is from the value discovery we discussed earlier:

“Don’t look for the needle in the haystack. Just buy the haystack!”

“On balance, the financial system subtracts value from society”

“The mutual fund industry has been built, in a sense, on witchcraft.”

“The grim irony of investing, then, is that we investors as a group not only don't get what we pay for, we get precisely what we don't pay for. So if we pay for nothing, we get everything.”

And perhaps the summary of everything that a passive tracker fund is:

“The index fund is a most unlikely hero for the typical investor. It is no more (nor less) than a broadly diversified portfolio, typically run at rock-bottom costs, without the putative benefit of a brilliant, resourceful, and highly skilled portfolio manager. The index fund simply buys and holds the securities in a particular index, in proportion to their weight in the index. The concept is simplicity writ large.”

The aim of this note is not to discuss the benefits or detriments of passive investing – we dealt with those points in our note on its unintended consequences. The aim is rather to highlight what is, and the reality is that whether we agree with the Buffett/Bogle passive approach is irrelevant.

The reality is that passive is increasingly dominant, and as far as we can see, the trend is unstoppable. The narrative of “set it and forget it” has enthralled a new generation of investors and wealth owners – millennials – and this shows up in the numbers. Based on data from Vanguard’s “How America Saves 2019” report, 60% of Vanguard’s 401K participants were solely invested in an automatic investment target date plan, with that number expected to go to 80% by 2023.

Let’s put this in perspective: if we can reasonably use Vanguard as the proxy for what the passive world is doing, then we’d expect that by 2023, 80c of every dollar invested goes into the same basket of instruments in the market, with that allocation based on predetermined weighting system defined by an index provider like MSCI.

When it comes to Millennials, the data suggests that everyone’s buying the same thing at the same time, since for every year you’re born in, in batches of 4 years, Vanguard defines a fund allocation for a specific target retirement date. Put differently, at every contribution date to a 401K plan, people born within each specific bracket of 4 years put their incremental savings into the same basket of stocks.

Tipping point.

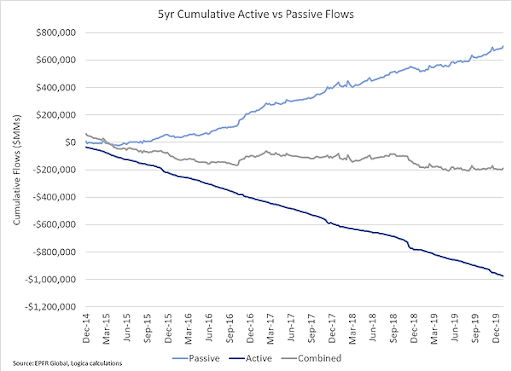

When we wrote our note on unintended consequences at the end of last year, things were hanging in the balance. The balance of active/passive flows in most of the world’s largest financial markets was at or around 50-50.

COVID-19 might have pushed this balance over to a passive-dominated market. While the story seems rosy for the Millennials, with steady contributions to their 401K plans even as we all work through the pandemic, the reverse isn’t true for the boomer generation. The older generation who believed and invested in actively managed funds – the same ones that try to find undiscovered opportunities to invest in, in the hope that everyone comes around to their point of view and bags them a neat profit – is cashing out, whether as they look forward to retirement or as they scramble to protect their savings as best they (believe) they can, in the face of unfamiliar and unprecedented volatility and uncertainty, in terms of both frequency and magnitude, in financial markets.

Given the following chart with data ranging till the end of 2019, again courtesy of Mike Green and team at Logica, one can only imagine that the gap is opening up even more:

Rage against the machine.

The next time you hear someone complaining about how illogical this market is, stop them for a moment and remind them that there’s no point being upset about a machine. It’s not human. Yet, it is 100% logical when it performs how it’s coded to.

In the case of a passive index tracker fund, it is important to remember that it doesn’t buy or sell based on value, none of this “buy low, sell high”, find the right value, DCF, fundamental analysis etc gibberish. No, a passive tracker fund buys when it receives inflows, and sells when it suffers outflows. What it buys is purely a function of what is on the list: in proportion, no more, no less.

In all likelihood, we are now way past that 50-50 balance between active and passive flows into the market. The passive way – buy on inflows, sell on outflows – increasingly dominates active discretion. If that is the case, then we need to take a very different view to managing money: stocks aren’t going up or down because of how much the underlying company earns (or loses), or how much dividends they pay (or don’t pay), or how much debt they owe.

That was how things used to be, when active discretionary managers (humans) dominated the flow and decision making in the markets. That age is probably gone. For now, the key is fund flows: where is the money flowing to, and what does it want to buy (hint: check the MSCI website).

Is the role of humans in the market completely over then? Definitely not. After all, as humans, there’s one edge we have over a machine code: the ability to change our minds, adapt, dream and imagine. Try being passive about that.