The Taming of the Dollar

2020 was without a doubt remarkable for an array of negative reasons. Perhaps 2020 will also be responsible for the rewriting of large swathes of theory around politics, economics and finance. From the uncanny correlations that have developed between prices of largely unrelated stocks that revealed the action of passive-driven market flows, to the bouts of volatility (or non-volatility) driven by hedging activity in the derivatives markets, the failure of financial markets in 2020 to conform to any semblance of “classical” economic theory should in itself be a strong signal that perhaps the theories are inadequate, incomplete or outright wrong.

We have penned our thoughts on all of the above at various times over the past few years, in our unending quest to understand and articulate our ever-evolving mental models on how things work. But perhaps somewhat silently, without as much fanfare, something else has been on the move.

In 2020 itself, the USD DXY index has posted a peak-trough depreciation of about 13%, pretty much in a single direction following the market lows in March 2020. Concurrently, the narratives in the market about the debasing of the US dollar started to pick up. As it stands, the DXY is at a pivotal level. The chart (as of the time of writing of this note, the day before markets reopen for 2021) says it all:

We think that proper thought needs to be given to the US Dollar and specifically what it means to be THE global reserve currency, what it takes to maintain that status and how its movements impact basically everything else.

Ultimately, understanding the possible outcomes the US dollar may face helps us to understand where the flow of money goes.

We are increasingly of the view that the policy actions taken especially in the US to counteract the impact of COVID-19 to the financial system has brought forward another inevitability which could have been stalled off for decades more: a mutually exclusive choice between US Dollar dominance and US Dollar strength.

The price of becoming indispensable.

A couple of weeks ago, we came across this particularly fascinating piece of reading entitled The Fraying of the US Global Currency Reserve System. It very much dovetailed into our prior work on how to value value, underscoring the importance of the historical context behind how we got to where we are today, with the USD as the world’s primary reserve currency.

The tipping point came after WW2. It was the first time in history that technology (in this case, military technology) allowed the whole world to be intertwined in one truly global war, which set the stage for a truly global monetary system to come in its wake.

When US came out of WW2 largely unscathed and the undisputed hegemon of the post-war order, it was natural to assume that as the only major intact global economy around, the Bretton Woods system of having all the world’s currencies pegged to the US Dollar (and gold) was the obvious solution to finding stability.

Yet as Bretton Woods ultimately broke down, defaulted upon by the US itself, the fundamental reason for its breakdown should have been taken as a warning against attempting to perpetuate USD dominance. The flaw in the system was what came to be known as the Triffin paradox.

Identified in the 1960s (prior to the fall of Bretton Woods in 1971) by economist Robert Triffin, the paradox points out that the country whose currency foreign nations wish to hold, must be willing to supply the world with an extra supply of its currency to fulfil world demand for these foreign exchange reserves – thus leading to a perpetual and growing external deficit.

Reframing the situation in this way perhaps adds another point to our growing collection of “involuntary” market actions: very much as options dealers hedge or passive funds involuntarily buy or sell at seemingly illogical prices, the US seems to be facing a situation where in order to maintain the US Dollar’s status as the global reserve currency, it is compelled to run an external deficit one way or another.

How else will they get additional dollars out into the world for other countries to hold as a reserve, over and above what is needed domestically?

As Bretton Woods crumbled, the replacement that took its place was the establishment of the petrodollar system, where US military protection for Saudi Arabia came in exchange for the use of the US Dollar in oil trading, helping to cement the US Dollar’s importance at the core of the global financial system.

That provided the nudge that was needed for countries to move to US Dollar reserves but the flipside of it was the subsequent and continuous appreciation of the US Dollar (despite being decoupled from its gold peg decades ago), accompanied by the ongoing “export” of US manufacturing capacity to the “Emerging” world, as the balancing term for a strong US Dollar AND a persistent external balance.

Summarising the thought process: US Dollar dominance as a reserve currency implies a need to send dollars out into the world. Sending dollars out means running an external deficit that is persistent (foreigners owning dollars = foreigners having a claim on US assets since every Dollar is an IOU on the Federal government) and the balancing term is the loss of something else – manufacturing perhaps.

So far, so good, but math always wins one way or another.

Musical Chairs

The problem that the US faces now is that Robert Triffin might be right, and that the thought process above pushes through to its eventual end point: a perpetual and growing external deficit that can no longer be funded.

While many accuse the US of abusing its dominance in order to borrow from the future and fund its hedonism to the point that there even exists a Wikipedia page for this “Exorbitant Privilege”, the counterargument we need to consider is this: the US has no choice but to run these deficits if it wants to maintain the US Dollar’s dominance.

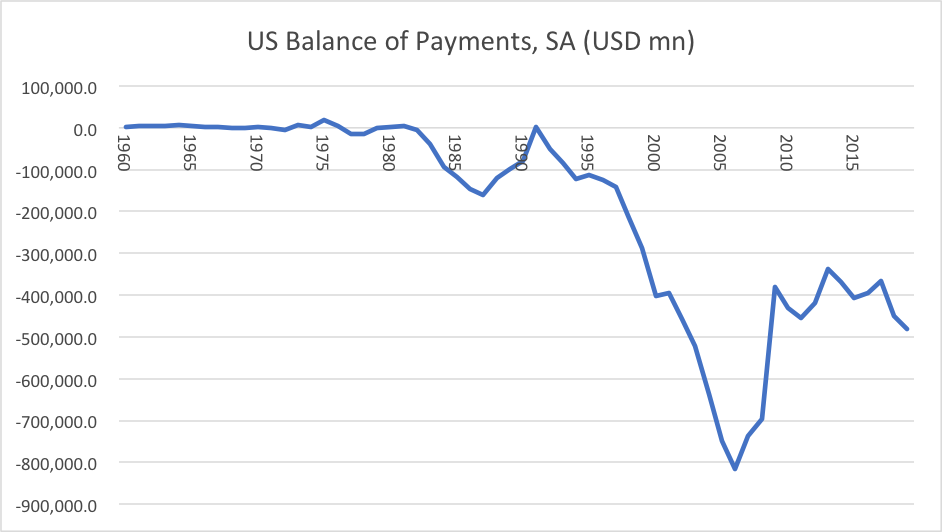

Source: OECD.Stat, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=MEI_BOP6#

For a long time, the world was happy to fund these deficits, especially when surplus US Dollars held in reserve was recycled back into buying US Treasuries, which in turn gave the debtholders (twice over now) a decent nominal return in a structurally disinflationary world.

Yet at current yields of around 1% on 10-year treasury debt, recycling surplus USD back to purchase the debt that funds the issuance of that same USD makes very little economic sense at all:

Source: OECD.Stat, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=MEI_BOP6#

Perhaps this goes a long way to explain how the Fed itself has turned into the US Treasury’s buyer of last resort:

Pulling forward eventualities

When people look back on 2020 and the impact of COVID-19 on the world economy, many will point to the silver lining of COVID-19 driven lockdowns pulling forward decades of adoption and demand of new technologies.

But perhaps what will be looked upon with a lot more consternation would be how COVID-19 also pulled in the runway that the US Dollar had at the top of the currency food chain. Maintaining an unstable equilibrium just got a little bit more tricky.

The monetary response from the Fed that came in March 2020, added to the jitters around liquidity that spurred the Treasury’s first response at the end of 2018 (when they were supposedly not concerned about liquidity) which itself marked the reversal the tightening stance of the Fed and consumed a huge proportion of whatever tiny buffer was left to make Treasuries (and US fixed income in general) palatable to arms-length investors.

As a result, the US Dollar faces an interesting scenario. While it remains THE dominant reserve currency in the world by virtue of it already being so, the reasons for which it may remain so are gradually dwindling. Ironically, by choosing not to have the US Dollar be THE dominant reserve currency globally, the US gives itself a chance to wind back its external liabilities and actually appreciate the US Dollar.

Politicians will probably have none of this though, with this view on full display in the opposition to Facebook’s Libra project – imagine what not having to supply US Dollars to all the world would do to the US external balance of payments! Furthermore, the mechanism by which US Dollars gets diverted back into either the US or into Treasuries would be even more unpalatable: interest rate hikes.

Which leaves us with the most likely eventuality: that in the absence of major systemic shocks (e.g. solvency issues or another market meltdown like we had in March 2020), all the US Dollars out there, outside the US, needs to find a new home that isn’t US Treasuries. Those Dollars are more likely than not to be sold for other forms of assets: for China, they find their way into the long term influence game of infrastructure projects along the Belt and Road. For others, commodities hard and soft, including Gold and for yet others Bitcoin is emerging as a possible alternative.

The latter arguably need little explanation, as would have already been obvious in mass media coverage over the past weeks. All of this combined was the opportunity we’ve imagined unfolding for years and to see it unfold before our eyes and be able to catch a sliver of it is deeply gratifying.

Re-Emerging Markets and the new kid on the block

Perhaps the biggest traditional beneficiary of abundant dollars in search of decent returns has been the world of emerging markets.

There’s just one caveat: while the need for a long set of trailing data means we are limited to using historical data for the MSCI EM ETF (EEM US), our views on the imbalanced representation of Chinese companies, especially Chinese Internet names, which we articulated before still stand, that the spirit of “Emerging Markets” is in fact very poorly captured by the outsized representation of China in the index weightings, not least because China itself can scarcely be classified as “emerging” in this day and age. That however does not stop the flows from cascading into a nicely packaged vehicle for allocators to buy.

For us, our reservations around taking outsized exposure to China can be reserved for another note, but it suffices to say at this point that our interest is in our long-time preferred hunting grounds in the likes of Indonesia, India, Brazil, Poland, Turkey and South Africa.

And finally enter the protagonist of the day: Bitcoin. Historically, as part of an asset allocator’s toolkit, the playbook was to buy EM and commodities when faced with a weak dollar. We are witnessing what appears to be a historic new entrant – an emerging financial asset on a tech-style adoption curve. Bitcoin’s price move has surprised everyone outside the crypto echo chamber but now it has entered mainstream adoption. This means the participants are changing. The base case now has to be that dollar weakness means Bitcoin strength or even that Bitcoin strength means dollar weakness! And with that the playbook is complete - for now.

Wherever we look, the same principles apply: we start with an idea and the multiple paths these ideas can take to materialise, and look to price action in the market to lead us to investment decisions that go with, rather than against, the market. Right now, that price action is pointing one way. How long does that last? We don’t worry about it. We set our risk levels and let the market take care of the rest.