Everything is a meme

Source: https://twitter.com/kofinas

Special mention once again to @JoshuaRosenthal whose work we reference extensively in this piece, especially for the last-minute expansion of his podcast episode with Bankless, which we have referenced and linked to below. Also thanks to @Fiskantes for the insights on memes, so clearly explained on this podcast with Uncommon Core.

“What is truth?”

For many, the ideal of truth is absolute: the earth orbits the sun and gravity pulls objects “down” towards the centre of the earth, for example. The presence of an absolute yardstick for what is and isn’t true sets a firm foundation for us to function, or what economists call “positive” statements – statements which can be empirically proven to be either true or untrue.

Of course, at the “personal” level, a philosophical argument could be made that everyone is entitled to opinions which can neither be proven nor disproven. Such statements are “normative”, and it is impossible for their validity to be comprehensively tested.

Historically, opinions remained largely in the realm of the personal. For everything else, the definition of truth was squarely in the control of the authorities: governments, the mainstream media and other organisations affiliated to or controlled by the state. All that the populace needed to know about the objective state of affairs came from these canonical sources of truth.

Then memes came along: these succinct, witty nuggets of messaging that require very little cognitive processing to understand. Memes came in different forms: we know them mostly as pictures that can be generated in a matter of minutes at Imgflip.com, but they can be anything from a short catchphrase (e.g. “Drain the swamp!” or “Full-self driving”) to a longer statement (e.g. “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.”) to ideologies of all shapes and sizes, some more unsavoury than others.

To some extent, memes are crude and simple – the image of a cute smiling dog, a filthy swamp that needs clearing up or the unsightly prospect of naked swimmers are, for example, what makes the messaging so easily comprehensible. They may be oversimplifications, but they certainly transmit message with much more efficacy and virality than a 60-page academic publication with an additional 12 pages of references and peer reviews.

Yet they are powerful: distributed widely enough, they are convincing devices of communication that allow “subjectively personal” opinions to go mainstream. What was previously the realm of testable, falsifiable “truth” is now increasingly opinionated.

This is also related to Ben Hunt’s work with Epsilon Theory and understanding the Zeitgeist, how themes like “Yay, Capitalism!” or “Yay, Value!” are crafted in a way that shapes our actual perception of reality. Yes, even at the highest levels of government and business, memes are very much in use – knowingly or otherwise.

The result: having an audience allows the lords and ladies of meme-ology to define a perception of absolute truth and reality for their followers. Everyone now has their own version of the truth.

That’s where things get tricky.

The first memelord

With 55.4m followers as of time of writing, Elon Musk is arguably today’s memelord supreme. His ability to dictate and inspire belief in a version of reality for his followers is perhaps, at this point, unrivalled. But contrary to public belief, memes are hardly a “modern” phenomenon. They are old.

And to get a quick flavour of the power of memes, we need to go back in time to the 1500s and look at the first memelord – a man called Lucas Cranach the Elder.

Few would have heard of him, although his close friend and contemporary Martin Luther would be a much more familiar name.

Courtesy of Josh Rosenthal, whose work was featured on his podcast with Bankless a couple of weeks ago (essential listening, if you haven’t already heard it), we are taken back to a time when knowledge and information were the reserve of the nobility. The printing press had only recently been invented, and until then all texts – religious, political or otherwise – had to be hand-copied by those (few) who could write and stored as precious artefacts in the libraries of monasteries and palaces. For the average person, life was pretty much static and truth was what your ruler, or the church, told you it was. Unimaginable to today’s world, being a priest was one of the best ways of social advancement – not only was it a route to an education, but it was also potentially a route to some degree of influence since the Roman Catholic church was at the time THE supreme political power in Europe.

Martin Luther was a German professor of theology and priest who, primarily in opposition to the practice of the church of selling plenary indulgences for cash, wrote a paper disputing the theological basis of such practices. He sent it to his Archbishop in 1517, which came to be known as the “Ninety-five Theses”. Legend holds that the Ninety-five Theses were nailed to the door of the All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg – whether it was true or just an embellishment of history, we will never know.

What we do know is that thanks to the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the early 1400s, the ability to distribute printed material was the fuel that allowed Luther’s thoughts – deemed heretical by the Vatican, the supreme power at the time to propagate across the continent, with translated copies from Latin to colloquial German spreading across Germany by early 1518 and reaching France, England and Italy by as early as 1519.

By middle-age standards, this was virality at its best. But what made these messages and ideas viral was not necessarily the text – it was the imagery that grew out of it. Just as it is now, a complex idea gets encapsulated in a meme that simplifies its consumption.

It was the memes that carried the potency of messaging to challenge what was established as universal truth at the time: the infallibility of Rome and the absolute monopoly on truth that the nobility and church had.

And here is where we meet perhaps the world’s first Memelord.

One of the most famous images that made the rounds was this, now known as “The Papal Belvedere”, a woodcut (for mass printing) made by Lucas Cranach the Elder, a close friend of Martin Luther, during the Lutheran Reformation after Luther had been condemned as a heretic, showing peasants farting at the pope and showing them their “belvedere” – a “beautiful view”:

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Papal_Belvedere.jpg

The text roughly translates to “The Pope speaks: Our sentences are to be feared, even if unjust. Response: Be damned! Behold, O furious race, my belvedere.” (Translation courtesy of the Wikimedia article – unfortunately, Latin isn’t our strong suite, so apologies for any mistranslation!)

Crude as it may be, images like this etched on wood allowed them to be replicated and printed with printing presses all over the continent and distributed with maximum virulence. The rest, as one would say, is history: the printing press created distribution, the memes created understanding and all it took was a message that resonated with the masses to trigger one of the biggest political and societal revolutions in history.

(21st May 2021 Update: It also follows that the counter to a meme is, most effectively, another meme. Josh Rosenthal’s thread here is a wonderful appendix to his podcast episode – with some true-to-form meme material, including more pre-renaissance prints, put in present-day context.)

The return of the meme

In this context, the art of the meme has arguably been around for centuries, evolving through the different stages of technological development – particularly technology for the distribution and dissemination of information.

The difference is that this time, the memes are not only everywhere, but they are also reaching into parts of society that sometimes do not even realise they’re being served with a meme. There are memes that are made as jokes, but the most profound are those that don’t even look like memes: from incendiary propaganda to systems of belief and stereotypes.

Whereas in the past the ability to control narratives (and most of the memes) was limited to the mainstream media, hence the media being termed the “Fourth Estate” (after the traditional three estates of the clergy, the nobles and the bourgeoisie), almost anyone can have a shot at gathering an audience now. Thanks to the internet, as well as platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Reddit and even 4chan, and armed with meme skills at their fingertips, influencers are able to shape public opinion around almost any topic with ease.

What started as clickbait material now has the ability to reshape truth. From echo chambers of political opinion to investment philosophy, the proliferation of memes is creating a world with multiple versions of truth – so many that there isn’t even a clear definition of what “truth” is anymore.

For example, is Bitcoin a “dirty currency”? The facts say no, but repeat a statistic about how Bitcoin mining consumes more electricity than many countries in the world enough times (especially on the Financial Times) and it becomes “dirty”. Facts are secondary. From “Drain the swamp” to “making humans a spacefaring civilization” (while spending Dogecoin on Mars?), it is increasingly clear that he who controls the biggest audience defines the greatest truth – even if a statement is patently falsifiable. And with voices bigger than what the “other side” can mount as a response, it is the loudest voice that wins the argument.

In the realm of financial markets, the memes too have rewritten the rules.

Once upon a time, truth was a case of finding value: ascertaining what a business was worth got us to the intrinsic value of a company’s equity or debt, allowing an investor to determine if something was over- or under-valued. Techniques and methodologies were created to calculate value, and university courses and textbooks were written for students who sought to learn these techniques.

Most importantly, everyone used to subscribe to the same standard of truth, that of “fundamental value”. This is unfortunately no longer the case. And for anyone who thinks that it still is (or that it should be because it’s the right thing) – things might get disappointing.

We have written about how market structure has given markets a life of their own, influenced by dealer hedges, passive flows and everything in between. Flows are the outcome, and behind those flows, the “value” meme is being replaced by other memes: saving the world, moving to mars, climate change or even just a cute dog, peddled by anyone from the memelords/ladies all the way down to the “furus” and their followers, and even governments, regulators and the established order.

Everyone’s playing the meme game now. Maybe “fundamental value” comes back (“Yay, Value!”), maybe it doesn’t, maybe it just come back for a while. Whatever it does, it is a function of the meme game, not the game itself.

This is our new reality – and in order to thrive, we, too, need to play the meme game.

Because if we are sitting and starting at the meme and don’t see it, then we’re the meme.

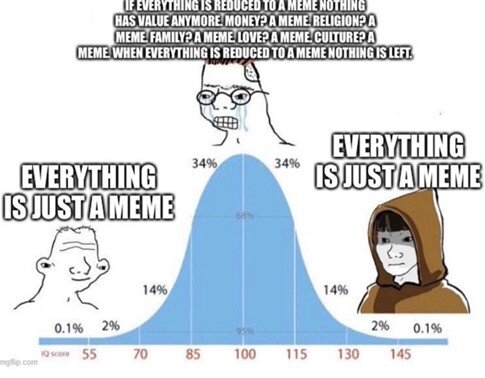

Everything is just a meme.

But few understand.